Women in the Alton Battalion

|

The topic of women soldiers disguised as men during the Civil War is a source of many fierce arguments, particularly in the realm of Civil War re-enacting.

Although as progressive living historians, the Alton Jaeger Guard does believe that women portraying men on the battlefield at living history events is overdone, and in most cases, completely baseless and historically inaccurate; we can not deny the fact that women DID in fact serve in the Civil War. According to the American Battlefield Trust, between 400 to 750 women fought as soldiers in the Civil War. The authors of the book "They Fought Like Demons: Women Soldiers in the American Civil War" give a different number though, stating that they found a total of 250 documented cases of women serving as soldiers. |

“The official records at Washington state that upward of 150 female recruits have been discovered since the commencement of the war. It is supposed that nearly all of these were in collusion with men who were examined and accepted, after which the fair ones managed to substitute themselves and be mustered into the service. Over seventy of these martial ladies, when their sex was discovered, were acting as officers servants. In one regiment there were seventeen of them in this capacity.”

Although the motives of these women surely varied on a case by case basis, records from the Alton Telegraph in 1864 show that women disguising themselves as men even occurred at the post in Alton, Illinois.

Although the motives of these women surely varied on a case by case basis, records from the Alton Telegraph in 1864 show that women disguising themselves as men even occurred at the post in Alton, Illinois.

This short, and particularly understated article was posted in the Alton Telegraph, during the war-time years:

FEMALE SOLDIERS ARRESTED

Alton Daily Telegraph, July 28, 1864

Three females in Federal uniform were arrested on the streets yesterday. They belonged to the 100 days men on duty at this post.

Alton Daily Telegraph, July 28, 1864

Three females in Federal uniform were arrested on the streets yesterday. They belonged to the 100 days men on duty at this post.

This short article is the only mention in the any local newspaper that mentions anything in regards to women dressed in federal uniform. The incident is not mentioned in any regimental history, or any other known court-martial paperwork, or criminal paperwork.

It is unknown which names these women may have enlisted as, or who they really were, or what happened to them after being arrested. The vague statement that the women belonged to the "100 Days Men" assigned to duty at Alton can lead the reader to guess that they could have been assigned to the "Alton Battalion", which were two companies organized in June of 1864 from Belleville and Mascoutah, Illinois. These two companies were initially recruited for 100 days service, and would form the first recruits of what would later become the 144th Illinois Infantry Regiment, which was organized to guard the prison in Alton, Illinois.

It is unknown which names these women may have enlisted as, or who they really were, or what happened to them after being arrested. The vague statement that the women belonged to the "100 Days Men" assigned to duty at Alton can lead the reader to guess that they could have been assigned to the "Alton Battalion", which were two companies organized in June of 1864 from Belleville and Mascoutah, Illinois. These two companies were initially recruited for 100 days service, and would form the first recruits of what would later become the 144th Illinois Infantry Regiment, which was organized to guard the prison in Alton, Illinois.

The following day after the Alton Telegraph published the article about the women being arrested, Pvt. James M. White, Co. A., Curtis's Company "Alton Battalion", wrote this Letter to the Editor:

Camp Platt, Alton, Illinois (Camp of 100-Day Volunteers)

Editor of the Democrat:

Alton Daily Telegraph, July 29, 1864

That miserable - and I might say contemptible - so-called Union paper, the Alton Telegraph, comes out in an article on yesterday and says that there are more soldiers here guarding prisoners than there are prisoners. Now, Mr. Editor, in the first place this is an infernal falsehood. There are fifteen hundred prisoners here, and but few more than three hundred soldiers to guard them. All men capable of doing duty are on duty every third day, and it takes 107 men per day to guard them. It is true we could guard 5,000 men, as easy as we guard 1,500, but they are not here, and it takes so many men to guard those that are.

And another infernal falsehood of that Union paper is that "three women dressed in Federal uniform, belonging to the 100-day men, were arrested in the streets yesterday." Now friend Democrat, there never was a more infernal slander upon the reputation of any than this. The men belonging to the 100-days volunteers at this post are all respectable men, and have as yet never disgraced themselves so much as to dress women in men's clothes and keep them as "kept women."

Now Mr. Editor, all that the Telegraph man is fit for is to encourage Abolitionists in destroying little one-horse country newspapers, and at the same time, abuse soldiers who they (the Telegraph) believe to be opposed to Mr. Lincoln. Now sir, should that paper attack us again, he will not get off so well as by a simple article through the paper.

Signed,

J. M. White, A 100-dayer

Editor of the Democrat:

Alton Daily Telegraph, July 29, 1864

That miserable - and I might say contemptible - so-called Union paper, the Alton Telegraph, comes out in an article on yesterday and says that there are more soldiers here guarding prisoners than there are prisoners. Now, Mr. Editor, in the first place this is an infernal falsehood. There are fifteen hundred prisoners here, and but few more than three hundred soldiers to guard them. All men capable of doing duty are on duty every third day, and it takes 107 men per day to guard them. It is true we could guard 5,000 men, as easy as we guard 1,500, but they are not here, and it takes so many men to guard those that are.

And another infernal falsehood of that Union paper is that "three women dressed in Federal uniform, belonging to the 100-day men, were arrested in the streets yesterday." Now friend Democrat, there never was a more infernal slander upon the reputation of any than this. The men belonging to the 100-days volunteers at this post are all respectable men, and have as yet never disgraced themselves so much as to dress women in men's clothes and keep them as "kept women."

Now Mr. Editor, all that the Telegraph man is fit for is to encourage Abolitionists in destroying little one-horse country newspapers, and at the same time, abuse soldiers who they (the Telegraph) believe to be opposed to Mr. Lincoln. Now sir, should that paper attack us again, he will not get off so well as by a simple article through the paper.

Signed,

J. M. White, A 100-dayer

It would appear that even during the Civil War, the topic of female soldiers was one of extreme controversy, and cloaked in denial.

Were there really three women serving in the Alton Battalion? Were they simply women dressing as soldiers for some other reason? Or is this all a lie from a sensationalist newspaper-man? According to Private White, it is the latter, however, today we will never know.

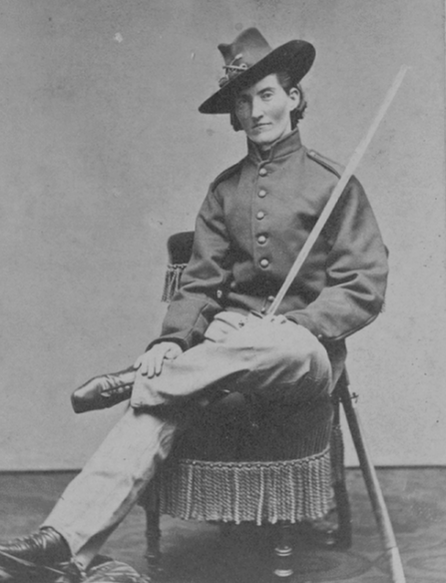

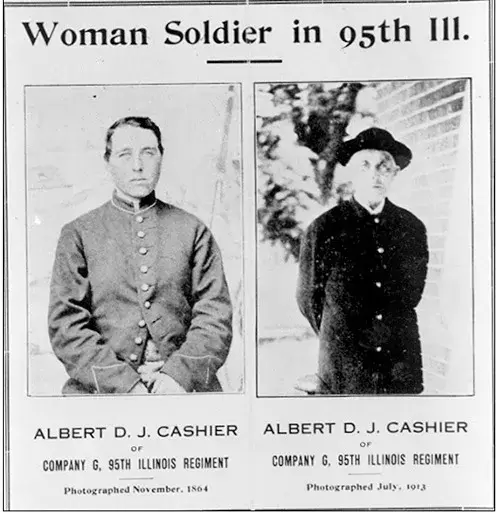

Photographs of Private Albert Cashier, born as Jennie Hodgers, volunteered to serve with Company G of the 95th Illinois Volunteer Infantry, and served throughout the war. Discovered to actually be a woman later in life, however, Albert lived his life as a man, and may be of the first known Transgender soldiers in the history of the US Military.

The following article from The National Parks Service, tells the story of one very real, and known female soldier who fought with bravery and distinction through the entire conflict.

Albert Cashier was born in 1843. He was assigned female at birth and given the name “Jennie Hodgers,” but at a young age began to dress as a boy and assumed a male identity. According to stories, Cashier’s step-father, short on money, dressed him as a boy to get a job. After Cashier’s mother died, he moved to Illinois and worked as a laborer, farmhand, and shepherd.

In August of 1862, "Private Albert D.J. Cashier" enlisted in the army at Belvidere, Illinois. Diminutive in size, Cashier resembled many Irishmen of the time. He continued to go unnoticed. No one thought anything of a quiet soldier seeking privacy for bathing and dressing. This was common. All in all, Cashier fought as an infantryman in forty battles. Even when receiving treatment for chronic diarrhea, his secret was not detected.

In May, 1863, Private Cashier participated in the Siege of Vicksburg, during which he was captured while performing a reconnaissance mission. He escaped by wrestling a gun away from a Confederate and was chased on foot, narrowly reaching the safety of the Union lines.

Private Cashier served a full enlistment. Even well after the war his comrades remembered the slight soldier as a brave fighter, admired for heroic actions and undertaking dangerous assignments, yet never receiving a scratch.

After the war Cashier returned to Illinois, taking work doing odd jobs for Illinois State Senator Ira Lish. On one fateful day, Senator Lish ran Cashier over with his car, breaking his leg. It was then that the town doctor discovered Cashier’s secret. Moved by Cashier’s pleas, the doctor agreed to maintain his confidence. This was a soldier with a pension. Had the secret been revealed, not only would the pension be revoked, but Cashier would have been forced to live as a woman. Cashier's leg never healed, and the Senator arranged for him to be placed in a rest home for veterans. While the staff was aware of Cashier's secret, they never broke his confidence.

Over time, Cashier’s physical and mental health deteriorated, and he was sent to the Watertown State Hospital for the Insane in 1914. Soon thereafter, facility staff discovered his secret. Newspapers leaked the story, which stirred controversy. The government charged Private Albert Cashier with defrauding the government to receive a military pension. An investigation was launched. Cashier’s comrades from the 95th Illinois rallied and testified that this was not Jennie Hodgers but Albert Cashier, a small but brave soldier who showed bravery on dangerous missions. In the end, Cashier maintained his veteran status. Despite this, he was kept in the mental institution and forced to wear women’s clothing. This took a great toll on his mental state. At 67 years old, frail and unaccustomed to walking in women's clothing, he tripped and broke his hip. He never recovered from the injury and spent the rest of his life bedridden and died on October 10, 1915. He was buried in uniform with full military honors. Many scholars suggest that if he had been alive today, Cashier may have identified as a transgender man.

Albert Cashier was born in 1843. He was assigned female at birth and given the name “Jennie Hodgers,” but at a young age began to dress as a boy and assumed a male identity. According to stories, Cashier’s step-father, short on money, dressed him as a boy to get a job. After Cashier’s mother died, he moved to Illinois and worked as a laborer, farmhand, and shepherd.

In August of 1862, "Private Albert D.J. Cashier" enlisted in the army at Belvidere, Illinois. Diminutive in size, Cashier resembled many Irishmen of the time. He continued to go unnoticed. No one thought anything of a quiet soldier seeking privacy for bathing and dressing. This was common. All in all, Cashier fought as an infantryman in forty battles. Even when receiving treatment for chronic diarrhea, his secret was not detected.

In May, 1863, Private Cashier participated in the Siege of Vicksburg, during which he was captured while performing a reconnaissance mission. He escaped by wrestling a gun away from a Confederate and was chased on foot, narrowly reaching the safety of the Union lines.

Private Cashier served a full enlistment. Even well after the war his comrades remembered the slight soldier as a brave fighter, admired for heroic actions and undertaking dangerous assignments, yet never receiving a scratch.

After the war Cashier returned to Illinois, taking work doing odd jobs for Illinois State Senator Ira Lish. On one fateful day, Senator Lish ran Cashier over with his car, breaking his leg. It was then that the town doctor discovered Cashier’s secret. Moved by Cashier’s pleas, the doctor agreed to maintain his confidence. This was a soldier with a pension. Had the secret been revealed, not only would the pension be revoked, but Cashier would have been forced to live as a woman. Cashier's leg never healed, and the Senator arranged for him to be placed in a rest home for veterans. While the staff was aware of Cashier's secret, they never broke his confidence.

Over time, Cashier’s physical and mental health deteriorated, and he was sent to the Watertown State Hospital for the Insane in 1914. Soon thereafter, facility staff discovered his secret. Newspapers leaked the story, which stirred controversy. The government charged Private Albert Cashier with defrauding the government to receive a military pension. An investigation was launched. Cashier’s comrades from the 95th Illinois rallied and testified that this was not Jennie Hodgers but Albert Cashier, a small but brave soldier who showed bravery on dangerous missions. In the end, Cashier maintained his veteran status. Despite this, he was kept in the mental institution and forced to wear women’s clothing. This took a great toll on his mental state. At 67 years old, frail and unaccustomed to walking in women's clothing, he tripped and broke his hip. He never recovered from the injury and spent the rest of his life bedridden and died on October 10, 1915. He was buried in uniform with full military honors. Many scholars suggest that if he had been alive today, Cashier may have identified as a transgender man.