Confederate Prison in Alton, Illinois

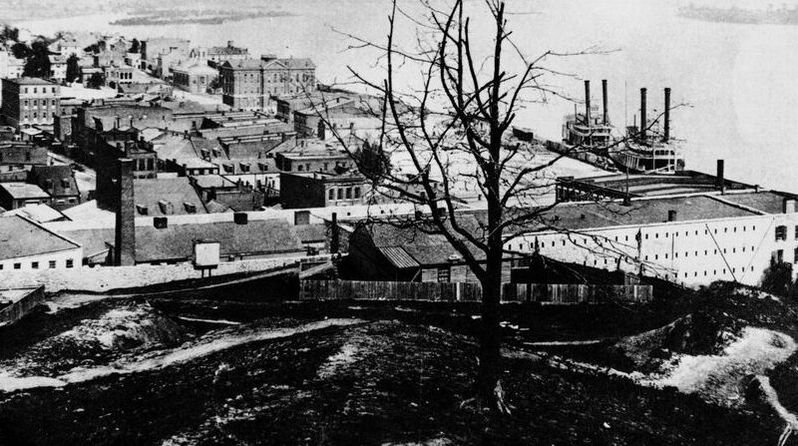

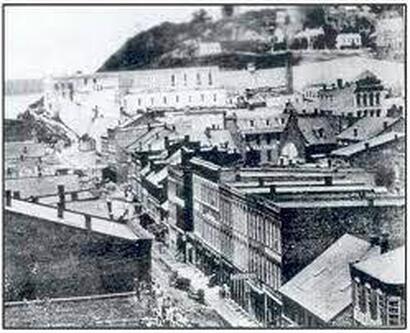

A view of the Alton Prison in 1861. The large white building just behind the log cabin in the foreground is the main blockhouse. The section on the right was the original tiers when the site was the State Penitentiary before the war.

During the Civil War, Alton was the site of one of the most infamous Confederate Prisoner of War camps, which was located in a former State Prison, erected along the Mississippi River, three decades prior. Thousands of men would lose their lives in this prison, but it's story does not begin in the Civil War.

In 1833, the State of Illinois opened its first State Penitentiary. The site chosen for this prison was Alton, Illinois. The first portion of the prison was built of stone and only had 24 cells. The prison cell-block was built on a hillside, within 100 yards of the Mississippi River. The yard of the prison extended down a hill, and the entire area was surrounded by large stone walls.

The prisoners were engaged in manual labor in the quarries near the prison, just West of the City of Alton, along the modern-day River Road. From 1835 to 1858 sixty-five women and three thousand men were sentenced to Alton.

In 1833, the State of Illinois opened its first State Penitentiary. The site chosen for this prison was Alton, Illinois. The first portion of the prison was built of stone and only had 24 cells. The prison cell-block was built on a hillside, within 100 yards of the Mississippi River. The yard of the prison extended down a hill, and the entire area was surrounded by large stone walls.

The prisoners were engaged in manual labor in the quarries near the prison, just West of the City of Alton, along the modern-day River Road. From 1835 to 1858 sixty-five women and three thousand men were sentenced to Alton.

|

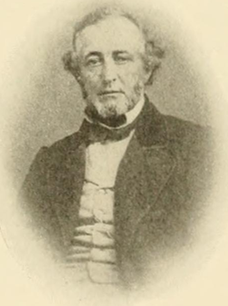

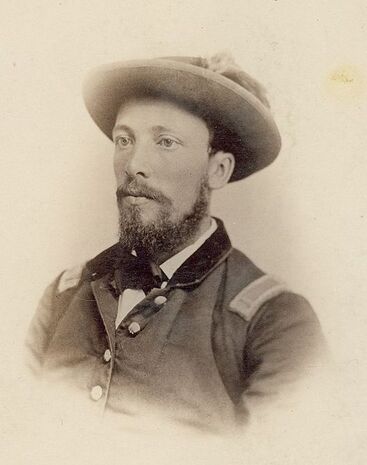

Colonel Samuel Buckmaster - Warden, Alton State Prison

|

Alton prison was known across the state for being a hard place to do time. And many prisoners would not survive even short sentences in Alton. In 1849, Cholera broke out at the prison among the inmates, and many lives were lost.

Additions were made to the prison throughout its years of occupation. In 1841, congress submitted a Bill to erect 94 additional cells and sheds, with the right to see excess land not needed for prison use. By the year 1857, the prison contained 256 cells. |

While the prison was used as a State Penitentiary, it was the source of many scenes of drama. One of the most peculiar incident occurred on March 9th 1858:

GUARD TAKEN PRISONER AT ALTON STATE PRISON

March 9, 1858

On March 9, 1858, a prisoner in the Alton State Prison by the name of Hall, from Chicago, was serving a second term for murder. After eating breakfast, no other guard was in the hallway surrounding the cells except for Clark C. Crabb, a family man living in Alton who worked as a prison guard. Hall knocked Crabb down and hit him in the head, stunning him insensible. Hall then dragged Crabb into one of the cells, tied his hands behind his back with strips of his blanket, and fastened the cell door closed with a piece of wood. Hall was armed with a large knife.

Colonel Samuel Buckmaster, warden of the prison, and some of the other guards, went to talk with prisoner Hall, who threatened to kill Crabb if any attempt was made to open the door. For over an hour, Colonel Buckmaster and his guards watched for an opportunity to shoot Hall, but there was only one small opening in the door, and Hall kept Crabb between him and that opening. When Crabb rose tried to get up to open the door, Hall cut him severely on the hand.

Hall demanded that he be given a revolver and ammunition, a full suit of clothes, $100, and to be driven out of town in a closed carriage, accompanied by Crabb. Buckmaster refused to give in. The warden obtained a pardon for Hall from the Governor, to be used at his discretion. All day and all night the guards were on watch to shoot Hall if they got the opportunity. The entrance to the cell was very narrow, and the door was made of plate iron, with a small grating at the top for ventilation. The door opened inwards, and was strongly fastened, so it was impossible to break it down.

At 9:00 a.m. on March 10, 1858, the State Prison Superintendent, Colonel Friend S. Rutherford, and Warden Colonel Samuel Buckmaster, came up with a plan. They brought breakfast to prisoner Hall, but in larger containers than normal. Hall refused to open the door until the hallway was cleared, however Rutherford, Buckmaster, and a few guards were on each side, out of sight and motionless. Hall slowly opened the door just enough to grab the food containers, and when he did, the hidden guards used a crowbar to block the door open. They shouted out for Crabb to fight for his life, and he sprang towards the opening. Crabb was eventually dragged through the door, but not before he was stabbed by the convict nine times in the back and twice on the arm. Hall immediately barred the door once again. The warden gave Hall a few minutes to reflect on his situation, and when he refused to submit, Hall was shot by Warden Buckmaster. The ball struck the skull just below the left ear. Hall’s body was drug out of the cell while he was yet alive and talking, and placed on a mattress in the hallway. Two knives were found on him – one eight inches long and doubled-faced, and the other four inches long. He exhibited no regrets or remorse, but that he hoped God would forgive him. He sent for one of his fellow-prisoners, and advised him to behave and not do as he had done. He was attended by a physician, but died later that day in the prison.

Prison guard Crabb was taken to the hospital and treated by Drs. Williams and Allen. The left lung had been perforated twice by the knife. His wife came to visit him, and he talked freely. It was doubtful that he would survive, given the severity of his wounds, but he did recover. Crabb later worked as a guard at the Joliet, Illinois, prison.

In July 1912, fifty-four years later, during the process of cleaning up the cellar at the George A. Sauvage cigar store on Piasa Street, a skull was found. It was determined to be that of prisoner Hall, the six-time murderer who tried to escape from the Alton State Prison by abducting prison guard Crabb. John Buckmaster formerly owned the cigar store, and inherited the skull from his father, Colonel Samuel Buckmaster, who was warden of the penitentiary at the time. Buckmaster kept the skull as a memento, and for years it served as a container for balls of twine. George Sauvage, when he purchased the cigar store, put the skull in the cellar. It is unknown why the skull was separated from the body of Hall, where the rest of his body was buried, and what happened to the skull after its discovery in 1912.

- Madison County IL GenWeb

March 9, 1858

On March 9, 1858, a prisoner in the Alton State Prison by the name of Hall, from Chicago, was serving a second term for murder. After eating breakfast, no other guard was in the hallway surrounding the cells except for Clark C. Crabb, a family man living in Alton who worked as a prison guard. Hall knocked Crabb down and hit him in the head, stunning him insensible. Hall then dragged Crabb into one of the cells, tied his hands behind his back with strips of his blanket, and fastened the cell door closed with a piece of wood. Hall was armed with a large knife.

Colonel Samuel Buckmaster, warden of the prison, and some of the other guards, went to talk with prisoner Hall, who threatened to kill Crabb if any attempt was made to open the door. For over an hour, Colonel Buckmaster and his guards watched for an opportunity to shoot Hall, but there was only one small opening in the door, and Hall kept Crabb between him and that opening. When Crabb rose tried to get up to open the door, Hall cut him severely on the hand.

Hall demanded that he be given a revolver and ammunition, a full suit of clothes, $100, and to be driven out of town in a closed carriage, accompanied by Crabb. Buckmaster refused to give in. The warden obtained a pardon for Hall from the Governor, to be used at his discretion. All day and all night the guards were on watch to shoot Hall if they got the opportunity. The entrance to the cell was very narrow, and the door was made of plate iron, with a small grating at the top for ventilation. The door opened inwards, and was strongly fastened, so it was impossible to break it down.

At 9:00 a.m. on March 10, 1858, the State Prison Superintendent, Colonel Friend S. Rutherford, and Warden Colonel Samuel Buckmaster, came up with a plan. They brought breakfast to prisoner Hall, but in larger containers than normal. Hall refused to open the door until the hallway was cleared, however Rutherford, Buckmaster, and a few guards were on each side, out of sight and motionless. Hall slowly opened the door just enough to grab the food containers, and when he did, the hidden guards used a crowbar to block the door open. They shouted out for Crabb to fight for his life, and he sprang towards the opening. Crabb was eventually dragged through the door, but not before he was stabbed by the convict nine times in the back and twice on the arm. Hall immediately barred the door once again. The warden gave Hall a few minutes to reflect on his situation, and when he refused to submit, Hall was shot by Warden Buckmaster. The ball struck the skull just below the left ear. Hall’s body was drug out of the cell while he was yet alive and talking, and placed on a mattress in the hallway. Two knives were found on him – one eight inches long and doubled-faced, and the other four inches long. He exhibited no regrets or remorse, but that he hoped God would forgive him. He sent for one of his fellow-prisoners, and advised him to behave and not do as he had done. He was attended by a physician, but died later that day in the prison.

Prison guard Crabb was taken to the hospital and treated by Drs. Williams and Allen. The left lung had been perforated twice by the knife. His wife came to visit him, and he talked freely. It was doubtful that he would survive, given the severity of his wounds, but he did recover. Crabb later worked as a guard at the Joliet, Illinois, prison.

In July 1912, fifty-four years later, during the process of cleaning up the cellar at the George A. Sauvage cigar store on Piasa Street, a skull was found. It was determined to be that of prisoner Hall, the six-time murderer who tried to escape from the Alton State Prison by abducting prison guard Crabb. John Buckmaster formerly owned the cigar store, and inherited the skull from his father, Colonel Samuel Buckmaster, who was warden of the penitentiary at the time. Buckmaster kept the skull as a memento, and for years it served as a container for balls of twine. George Sauvage, when he purchased the cigar store, put the skull in the cellar. It is unknown why the skull was separated from the body of Hall, where the rest of his body was buried, and what happened to the skull after its discovery in 1912.

- Madison County IL GenWeb

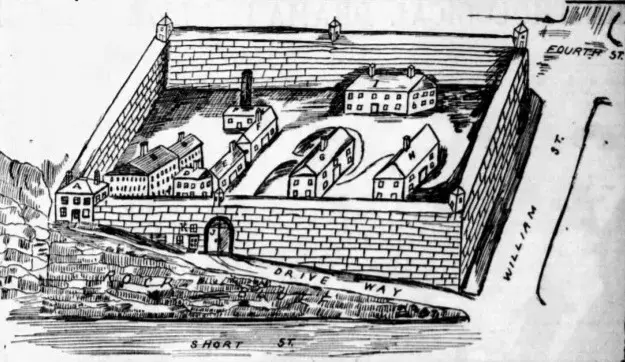

19th Century artists depiction of the Alton Penitentiary as it appeared in operation.

The Mississippi River was just below Short St.

The Mississippi River was just below Short St.

The prison had a main, 3-story penitentiary building containing 256 cells, which was the original prison blockhouse. Each cell measured about 4x7 feet. There were also 5 large rooms divided by partitions, this provided 2 enclosures each. Of the 2 enclosures, one measured 7x4 feet and the other one was 20x4 feet.There were several other buildings in the yard, enclosed by a large stone wall.

One of the buildings was a 2-story wood-frame measuring 46x97 feet on the first floor and 46 sq. feet on the second floor. There was an old 2-story stable measuring 29x49 feet on each floor. Two other buildings were used for confining Union troops held under court-martial, 50x103 foot building, and some civilian prisoners, 50x36 foot building.

The maximum capacity was estimated at 800 prisoners.

The prison hospital began as a room in the main prison building. As illness among the prisoners increased, the hospital grew and included 2 converted workshops in the prison yard. The bodies of the dead prisoners were kept in the prison "deadhouse" until they could be buried.

The prison operated from 1833 until 1860. In 1855, prison reformer Dorthea Dix visited the prison in Alton, and determined it to be inhumane and wrote a devastating report, demanding the prison be closed down. Decades of heavy use, which included several fires, wall collapses and even riots, had deteriorated the prison was declared condemned and the State of Illinois decided to close the prison down, build a new facility in Joliet, Illinois. The last prisoners left Alton for Joliet in 1860.

The former Warden of the Alton State Prison, Col. Buckmaster, was also instrumental in the early days of the Civil War, as he personally took a steamer to St. Louis, MO from Alton, IL when the St. Louis Arsenal was emptied to keep out of Confederate hands. The arms were handed off to Buckmaster's men aboard the ship, and brought back across the river to Alton.

One of the buildings was a 2-story wood-frame measuring 46x97 feet on the first floor and 46 sq. feet on the second floor. There was an old 2-story stable measuring 29x49 feet on each floor. Two other buildings were used for confining Union troops held under court-martial, 50x103 foot building, and some civilian prisoners, 50x36 foot building.

The maximum capacity was estimated at 800 prisoners.

The prison hospital began as a room in the main prison building. As illness among the prisoners increased, the hospital grew and included 2 converted workshops in the prison yard. The bodies of the dead prisoners were kept in the prison "deadhouse" until they could be buried.

The prison operated from 1833 until 1860. In 1855, prison reformer Dorthea Dix visited the prison in Alton, and determined it to be inhumane and wrote a devastating report, demanding the prison be closed down. Decades of heavy use, which included several fires, wall collapses and even riots, had deteriorated the prison was declared condemned and the State of Illinois decided to close the prison down, build a new facility in Joliet, Illinois. The last prisoners left Alton for Joliet in 1860.

The former Warden of the Alton State Prison, Col. Buckmaster, was also instrumental in the early days of the Civil War, as he personally took a steamer to St. Louis, MO from Alton, IL when the St. Louis Arsenal was emptied to keep out of Confederate hands. The arms were handed off to Buckmaster's men aboard the ship, and brought back across the river to Alton.

|

In 1861, war broke out across the country. Alton's prison was once again occupied, this time by Federal troops from the 7th Regiment of Illinois Volunteer Infantry. It was felt that Alton stood at a strategic point along the Mississippi River, and a garrison was needed.

The men of the 7th Illinois Infantry were not exactly pleased at their first assignment being the former State Prison which was deemed unfit for murderers and rapists, but fit enough for Illinois Volunteers. Eventually the 7th would appreciate their time in Alton, and would often drill and march through town, much to the enjoyment of the citizens of Alton. Especially popular was the "Springfield Greys" a company of the 7th whom previously to taking the oath, were part of an elite militia unit from Springfield, Illinois. |

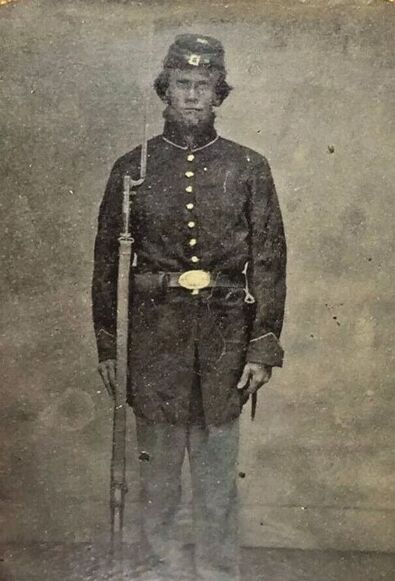

A Private in the "Springfield Greys" in 1861.

|

While the 7th Illinois garrisoned the prison, they used their time in Alton to continue recruiting, and the regiment was at full strength when it left its post, even with the men who resigned due to their dissatisfaction of being assigned to a prison.

This was the first time that the citizens of Alton would see a military occupation, however it would be a site that would become the norm as the war continued. It wouldn't be until 1865 that soldiers wouldn't be a daily sight on Alton's streets.

This was the first time that the citizens of Alton would see a military occupation, however it would be a site that would become the norm as the war continued. It wouldn't be until 1865 that soldiers wouldn't be a daily sight on Alton's streets.

7TH ILLINOIS REGIMENT QUARTERS AT ALTON PRISON

Source: History of the 7th Regiment, Illinois Volunteer Infantry, April 25, 1861 to July 9, 1865

D. Leib Ambrose, 1868

At this time the firm steps of Illinois patriot men were heard keeping step to the music of the Union. In every direction her stalwart sons were seen marching towards the Capital. The loyal pulse never beat so central and quickening as at this period.

After the organization of the regiment on 27th March, they are marched from Camp Yates to the armory, where they receive their arms - the Harper's Ferry altered musket - after which the regiment marches to the depot and embarks for Alton, Illinois where the regiment arrives at 4 p.m., April 25, 1861 and are quartered in the old State Penitentiary. With men who were eager for war, whose hopes of martial glory ran so high, to be quartered in the old criminal home grated harshly, and they did not enter those dark recesses with much gusto.

During our stay here, the regiment was every day marched out on the city commons by Colonel Cook, and there exercised in the manual of arms and the battalion evolution until they attained a proficiency surpassed by none in the service. On the 19th of May, Private Harvey of Company A, died the first death in the regiment. The first soldier in the first regiment to offer his life for the flag and freedom. On June 2nd, Private Dunsmore of the same company falls into a soldier's grave. May the loyal people ever remember these first sacrifices so willingly offered in the morning of the rebellion.

On July 3rd, 1861, the regiment embarked on board the steamer "City of Alton" for Cairo, Illinois. Passing down the river, the steamer is hailed and brought to at the St Louis Arsenal and after the necessary inspection proceeds on her way.

Source: History of the 7th Regiment, Illinois Volunteer Infantry, April 25, 1861 to July 9, 1865

D. Leib Ambrose, 1868

At this time the firm steps of Illinois patriot men were heard keeping step to the music of the Union. In every direction her stalwart sons were seen marching towards the Capital. The loyal pulse never beat so central and quickening as at this period.

After the organization of the regiment on 27th March, they are marched from Camp Yates to the armory, where they receive their arms - the Harper's Ferry altered musket - after which the regiment marches to the depot and embarks for Alton, Illinois where the regiment arrives at 4 p.m., April 25, 1861 and are quartered in the old State Penitentiary. With men who were eager for war, whose hopes of martial glory ran so high, to be quartered in the old criminal home grated harshly, and they did not enter those dark recesses with much gusto.

During our stay here, the regiment was every day marched out on the city commons by Colonel Cook, and there exercised in the manual of arms and the battalion evolution until they attained a proficiency surpassed by none in the service. On the 19th of May, Private Harvey of Company A, died the first death in the regiment. The first soldier in the first regiment to offer his life for the flag and freedom. On June 2nd, Private Dunsmore of the same company falls into a soldier's grave. May the loyal people ever remember these first sacrifices so willingly offered in the morning of the rebellion.

On July 3rd, 1861, the regiment embarked on board the steamer "City of Alton" for Cairo, Illinois. Passing down the river, the steamer is hailed and brought to at the St Louis Arsenal and after the necessary inspection proceeds on her way.

On December 31, 1861, Maj. Gen. Henry Halleck, Commander of the Department of the Missouri, ordered Lt. Col. James McPherson to Alton for an inspection of the closed penitentiary. McPherson reported that the prison could be made into a military prison and house up to 1,750 prisoners with improvements. The abandoned Alton Prison was taken over by authorities in January of 1862. The first prisoners arrived at Alton Prison on February 9, 1862.

PRISONERS TO BE BROUGHT TO ALTON

Source: Alton Telegraph, January 17, 1862

We were informed this morning that it was noticed that the prisoners now confined in McDowell’s College in St. Louis are to be brought to Alton, and enclosed in the old Penitentiary. The great many of our citizens appear to apprehend the most fearful consequences to result from this act. They contend that the people of Missouri will be so enraged that they will close the river and fire the town, and commit other depredations upon the property of the citizens. There is much talk of calling a public meeting to protest against their being brought. One thing is evident, that they either ought not to be moved here, or, if they are, the government should garrison the place with a sufficient number of soldiers to protect the city against outrages from the other side of the river.

PENITENTIARY CONVERTED TO MILITARY PRISON

Source: Liberty Weekly Tribune, January 31, 1862

The old Illinois Penitentiary buildings at Alton will be converted into a military prison, General Halleck having notified parties at Alton to have the buildings prepared for the reception of the 1,200 prisoners lately captured by Gen. Pope's command.

Source: Alton Telegraph, January 17, 1862

We were informed this morning that it was noticed that the prisoners now confined in McDowell’s College in St. Louis are to be brought to Alton, and enclosed in the old Penitentiary. The great many of our citizens appear to apprehend the most fearful consequences to result from this act. They contend that the people of Missouri will be so enraged that they will close the river and fire the town, and commit other depredations upon the property of the citizens. There is much talk of calling a public meeting to protest against their being brought. One thing is evident, that they either ought not to be moved here, or, if they are, the government should garrison the place with a sufficient number of soldiers to protect the city against outrages from the other side of the river.

PENITENTIARY CONVERTED TO MILITARY PRISON

Source: Liberty Weekly Tribune, January 31, 1862

The old Illinois Penitentiary buildings at Alton will be converted into a military prison, General Halleck having notified parties at Alton to have the buildings prepared for the reception of the 1,200 prisoners lately captured by Gen. Pope's command.

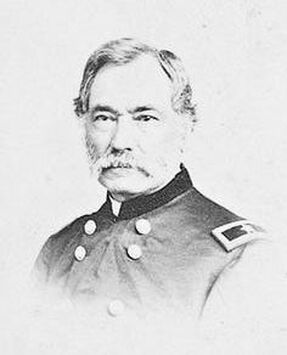

The first unit assigned to guard the prison was the 13th U.S. Regulars, under Colonel Sidney Burbank. The 13th U.S. stood in stark comparison to the mostly untrained recruits from the 7th Illinois Volunteer Infantry. These "Regulars" would be present for the arrival of the first prisoners in the camp.

|

Colonel Sidney Burbank - Commander, 13th US Regulars

|

The 13th US Infantry would watch the prison go from nearly empty to overfilled within the course of several weeks.

After the Battle of Fort Donelson, nearby Gratiot Prison in St. Louis was overflowing, and hundreds of Confederate prisoners captured in the fighting at Donelson would end up in Alton. By May of 1862, the Alton Prison would begin to see its first cases of smallpox, which would ultimately be what would give the prison it's grisly and infamous reputation. |

While the 13th US was guarding the prison, several famous prisoners would make it through the gates of the Alton Prison, including Confederate General Edwin Price, the son of Major General Sterling Price.

On August 1st 1862, Confederate prisoners dug a tunnel under the wall, within feet of a sentry post. During the morning hours, 35 prisoners escaped and fled across the river to Missouri. The men were quickly apprehended, however it was an embarassing moment for Burbank's command, and he and the 13th US Regulars would shortly thereafter, be transferred to Virginia, where they would serve in the Eastern Theater of war.

On August 1st 1862, Confederate prisoners dug a tunnel under the wall, within feet of a sentry post. During the morning hours, 35 prisoners escaped and fled across the river to Missouri. The men were quickly apprehended, however it was an embarassing moment for Burbank's command, and he and the 13th US Regulars would shortly thereafter, be transferred to Virginia, where they would serve in the Eastern Theater of war.

In August of 1862, the men of 77th Ohio Volunteer Infantry Regiment, under the command of Colonel Jess Hildebrand would arrive in Alton, and Colonel Hildebrand would take command of the prison. The 77th Ohio Volunteers were already a war-torn and bloodied unit by the time they arrived in Alton.

|

Colonel Jesse Hildebrand - Commander, 77th Ohio Volunteer Infantry

|

The regiment took extremely heavy casualties at Shiloh, and between April 6 and 8, the regiment had 50 men killed, 114 men wounded, and 56 men missing or captured.

After Shiloh, the regiment took part in the Battle of Corinth, they were detailed to Memphis to repair railroads for two months. The men of the 77th Ohio hoped that Alton would be a welcome reprieve from the hardships they had experienced on campaign. Ironically for the men of the 77th Ohio, many of the prisoners who would be in their care would be the very same men they had just shared battlefields with at Shiloh and Corinth. |

The men of the 77th Ohio seemed to enjoy themselves, in particular, Alton's "red light district", which was only one street over from, and ran parallel to the prison. This is evident by this standing order given by Colonel Hildebrand to his men:

GENERAL ORDER FROM THE ALTON MILITARY POST

Headquarters, 77th Regiment Ohio Volunteers Infantry

Alton Telegraph, October 31, 1862

All persons engaged in selling, or who keep spiritous or malt liquors in the city or vicinity of Alton, Illinois, are hereby strictly forbidden the selling or giving to any soldier, or suffering any soldier to drink any spiritous or malt liquors about his premises, under the ponsity of having his house closed, all his liquors confiscated, and he himself be imprisoned or otherwise punished if the circumstances may require.

Any officer or soldier attached to or belonging to the Military Post at Alton, Illinois, or remaining temporarily in the city, being found intoxicated, will immediately be arrested and punished by the penalty of confinement in the cells, or placed under arrest to be punished as a military court may determine; and shall be deprived of his or their liberty until he or they shall have given information where they received said intoxicating drinks.

And any non-commissioned officer, musician, or private, who may be found guilty of trading, selling, or spawning any military clothing, equipment or Government property of any kind, shall be punished to the extreme penalty of the law; and I do hereby warn and forbid all persons from buying, trading, or bartering with soldiers for such articles, and all citizens are strictly forbid wearing the whole, or any part of, a soldier’s uniform.

Signed by J. Hildebrand,

Colonel, Commanding Post.

Headquarters, 77th Regiment Ohio Volunteers Infantry

Alton Telegraph, October 31, 1862

All persons engaged in selling, or who keep spiritous or malt liquors in the city or vicinity of Alton, Illinois, are hereby strictly forbidden the selling or giving to any soldier, or suffering any soldier to drink any spiritous or malt liquors about his premises, under the ponsity of having his house closed, all his liquors confiscated, and he himself be imprisoned or otherwise punished if the circumstances may require.

Any officer or soldier attached to or belonging to the Military Post at Alton, Illinois, or remaining temporarily in the city, being found intoxicated, will immediately be arrested and punished by the penalty of confinement in the cells, or placed under arrest to be punished as a military court may determine; and shall be deprived of his or their liberty until he or they shall have given information where they received said intoxicating drinks.

And any non-commissioned officer, musician, or private, who may be found guilty of trading, selling, or spawning any military clothing, equipment or Government property of any kind, shall be punished to the extreme penalty of the law; and I do hereby warn and forbid all persons from buying, trading, or bartering with soldiers for such articles, and all citizens are strictly forbid wearing the whole, or any part of, a soldier’s uniform.

Signed by J. Hildebrand,

Colonel, Commanding Post.

In July of 1863, the 37th Iowa Volunteer Infantry Regiment, with Colonel George Kincaid in command, arrived in Alton and took over guard duties at the prison. Known as “The Graybeard Regiment”, this regiment was unique in that it was composed almost entirely of men not fit for military service. All men enlisted had to be at least 45 years old. It spent most of its service guarding prisoner of war camps and supply trains.

|

Private Thomas Weatherax

Co. A., 37th Iowa Volunteers "Graybeards" |

The regiment was created for political reasons as a way of proving that men well above normal military age were willing to volunteer. While most of its members were in their 40s, 50s, and 60s, it is recorded that a few were in their 70s and at least one man claimed to be 80.

The 37th Iowa was the least effective of the units assigned to Alton for guard duties. Their commander was rumored to be a corrupt officer and even committed a type of water boarding on some prisoners. During one month alone, 23 Confederate prisoners of war escaped from the jail, unnoticed by the Greybeards. The "Graybeards" also had the unfortunate luck of serving during the most difficult time in the prison's history. The men of the 37th Iowa suffered more casualties in Alton, than any other regiment assigned. |

THE GREY BEARDS OF IOWA

Alton Telegraph, January 1, 1864

To the Editor of the Telegraph –

Thousands both in civil and military life, even in the western country, have but an imperfect knowledge of the above regiment. We only purpose to present to give a brief, but authentic account of it. In the month of July 1862, when the whole nation was moved with the spirit of war, there sat a man in deep and silent reflection on the sad and calamitous event of the country. Shall the Stars and Stripes, whose hallowed folds I have nestled in safety for half a century, now be insulted and defied by foes at home and abroad? I prefer death rather than see conquest by the enemies of my country. But what can I do to help in the subjugation of invading enemies? The patriot’s heart was moved to its depths with anxiety, and while in that state, a thought momentous, in its consequence, flashed upon his mind, that thought was sustained, it increased in intensity until it electrified every part of the man, and he stood in fancy in the midst of a regiment of self-sacrificing men, who had battled with the common vicissitudes of life for three score years. In less than ninety days after the conception of the idea of an old man’s regiment, George W. Kincaid stood – not in fancy’s vision, but in joyful reality, in the midst of the 37th Iowa Regiment, honored as its chief commander. To get up a regiment of men over forty-five years of age in the young State of Iowa seemed to many a matter next to impossible, but Mr. Kincaid thought differently. He corresponded with the proper authorities upon the subject of some man in the State being appointed to raise a regiment of men exempt from military duty on account of their age. Mr. Kincaid was solicited to accept said commission, which he finally consented to do. And went to work with a will, resolved that if energy and perseverance could accomplish the work, the formation of such a regiment would be a success.

Men of ability and experience came to his aid, and as fast as the intelligence spread through the country, that the father as well as their sons should have the privilege of bearing arms in a distinct regiment, in the defense of their country, hundreds seemed to renew their age at the call of their country. The embers of patriotism were fanned to a mighty flame, while the impassioned eloquence of the heart was heard thundering from every tongue, long wave the Stars and Stripes. Home and kindred were felt cheerfully to endure the toils and perils of a soldier’s life. The companies were formed in different parts of the State, and so rapid were the enlistments that the various companies were ordered into quarters at Camp Strong, Muscatine, Iowa, in the month of October 1862. In the month of December following, the regiment was mustered into the United States service by Captain H. B. Hendershott. The regiment was ordered to St. Louis, where it arrived January 1, 1863, passing through the city to Benton Barracks. Being ordered into the city to Schofield Barracks, the regiment took possession of the same, January 4, 1863.

After enjoying city life for about five months, the regiment was ordered to do guard duty on the Pacific and Rolla railroad, where they spent some two months very pleasantly among the citizens, no trouble occurring whatever. The regiment receiving orders to move, it left for Alton, Illinois, where it arrived July 30, 1863.

This regiment is a military curiosity, the age of the men ranging from 45 to 80, the average age being about 55. Never in the history of civilization was a regiment of men gotten up for the purpose of war of the above ages. The 37th Iowa was not made up of the scum and washings of society, as a few uninformed persons have supposed, neither of that class of persons dependent on the army of the poor house for subsistence. Just the reverse of this are the facts in the case. A great majority left comfortable and happy homes – many their farms, shops and merchandise businesses that amounted to thousands per annum. There are a number of privates worth from five to forty thousand dollars, cheerful and happy to serve their country in that honorable capacity; men of good minds and respectable information. It must be expected that in a body of men numbering so many hundreds, gathered promiscuously from the State, born and educated in different nations, each one having his own belief, politics, and religion, and the rules by which society should be governed; with the fixed habits of more than a half century unaccustomed to the rules and laws that regulate military life; that in the government and necessary discipline of such a body of men a little friction would occasionally take place. It is a matter of surprise to every reflecting mind conversant with the regiment, that so much harmony and promptness to obey orders, and general good conduct has prevailed among the men. This in a great measure is the result of the mental and moral qualities of those in command. To the honor and credit of the Commander in Chief of the regiment, be it said, that a large proportion of the family of commissioned officers are men that teach morality and virtue, both by precept and example. The Colonel’s staff is composed of men possessing clear heads and sound bodies; men from the active business walks of life, thoroughly competent to discharge the duties devolving upon them in their respective positions. The raising, equipping, and placing the above regiment in the service of the United States was considered a military experiment. It is very gratifying to those who labored day and night for its existence that the project has proved a glorious success. No body of young men in the same capacity have done more efficient work than the Grey Beards. Every officer, whether high or low in command charged with any important trust, has in every instance given entire satisfaction.

The health of the regiment taken through all the seasons of the year will tally with any other in the service. In regard to the number of deaths, they have been less than in most other regiments. And considering the ages of the men, their exposure to all kinds of weather, the amount of labor performed, the preservation of life and health is truly wonderful. Hundreds who taste nothing stronger than tea or coffee enjoy the envied prize of sparkling eyes and rosy cheeks, with a youthful and happy flow of spirits. Should an occasion ever offer itself for these silver-haired patriots to exhibit their pluck and fortitude on the field of blood and carnage, they will be found equal to any heroes that ever drew a sword or cocked a musket. At present, the regiment numbers about seven hundred men, and taking them as a whole, are enjoying fine health and spirits. The men have received their bounty, and all other claims and demands the government has promptly met. Any government whose laws and institutions are so sacred and highly prized as to cause men voluntarily of three score years and ten to leave all the endearments and luxuries of home, giving health and life, if need be, to save that country from desolation and ruin; any nation possessing such elements of power can safely calculate on its strength and perpetuity. Well may the youthful State of Iowa be proud of the honor of sending one of the most extraordinary regiments into the service of the United States government the sun ever shone upon. Historic page will faithfully record their doings, and when they shall have gone to sleep with their fathers, then their posterity will chant in poetic song, the patriotism of their noble and worthy ancestors.

Signed, Justice

Alton, December 25, 1863

Alton Telegraph, January 1, 1864

To the Editor of the Telegraph –

Thousands both in civil and military life, even in the western country, have but an imperfect knowledge of the above regiment. We only purpose to present to give a brief, but authentic account of it. In the month of July 1862, when the whole nation was moved with the spirit of war, there sat a man in deep and silent reflection on the sad and calamitous event of the country. Shall the Stars and Stripes, whose hallowed folds I have nestled in safety for half a century, now be insulted and defied by foes at home and abroad? I prefer death rather than see conquest by the enemies of my country. But what can I do to help in the subjugation of invading enemies? The patriot’s heart was moved to its depths with anxiety, and while in that state, a thought momentous, in its consequence, flashed upon his mind, that thought was sustained, it increased in intensity until it electrified every part of the man, and he stood in fancy in the midst of a regiment of self-sacrificing men, who had battled with the common vicissitudes of life for three score years. In less than ninety days after the conception of the idea of an old man’s regiment, George W. Kincaid stood – not in fancy’s vision, but in joyful reality, in the midst of the 37th Iowa Regiment, honored as its chief commander. To get up a regiment of men over forty-five years of age in the young State of Iowa seemed to many a matter next to impossible, but Mr. Kincaid thought differently. He corresponded with the proper authorities upon the subject of some man in the State being appointed to raise a regiment of men exempt from military duty on account of their age. Mr. Kincaid was solicited to accept said commission, which he finally consented to do. And went to work with a will, resolved that if energy and perseverance could accomplish the work, the formation of such a regiment would be a success.

Men of ability and experience came to his aid, and as fast as the intelligence spread through the country, that the father as well as their sons should have the privilege of bearing arms in a distinct regiment, in the defense of their country, hundreds seemed to renew their age at the call of their country. The embers of patriotism were fanned to a mighty flame, while the impassioned eloquence of the heart was heard thundering from every tongue, long wave the Stars and Stripes. Home and kindred were felt cheerfully to endure the toils and perils of a soldier’s life. The companies were formed in different parts of the State, and so rapid were the enlistments that the various companies were ordered into quarters at Camp Strong, Muscatine, Iowa, in the month of October 1862. In the month of December following, the regiment was mustered into the United States service by Captain H. B. Hendershott. The regiment was ordered to St. Louis, where it arrived January 1, 1863, passing through the city to Benton Barracks. Being ordered into the city to Schofield Barracks, the regiment took possession of the same, January 4, 1863.

After enjoying city life for about five months, the regiment was ordered to do guard duty on the Pacific and Rolla railroad, where they spent some two months very pleasantly among the citizens, no trouble occurring whatever. The regiment receiving orders to move, it left for Alton, Illinois, where it arrived July 30, 1863.

This regiment is a military curiosity, the age of the men ranging from 45 to 80, the average age being about 55. Never in the history of civilization was a regiment of men gotten up for the purpose of war of the above ages. The 37th Iowa was not made up of the scum and washings of society, as a few uninformed persons have supposed, neither of that class of persons dependent on the army of the poor house for subsistence. Just the reverse of this are the facts in the case. A great majority left comfortable and happy homes – many their farms, shops and merchandise businesses that amounted to thousands per annum. There are a number of privates worth from five to forty thousand dollars, cheerful and happy to serve their country in that honorable capacity; men of good minds and respectable information. It must be expected that in a body of men numbering so many hundreds, gathered promiscuously from the State, born and educated in different nations, each one having his own belief, politics, and religion, and the rules by which society should be governed; with the fixed habits of more than a half century unaccustomed to the rules and laws that regulate military life; that in the government and necessary discipline of such a body of men a little friction would occasionally take place. It is a matter of surprise to every reflecting mind conversant with the regiment, that so much harmony and promptness to obey orders, and general good conduct has prevailed among the men. This in a great measure is the result of the mental and moral qualities of those in command. To the honor and credit of the Commander in Chief of the regiment, be it said, that a large proportion of the family of commissioned officers are men that teach morality and virtue, both by precept and example. The Colonel’s staff is composed of men possessing clear heads and sound bodies; men from the active business walks of life, thoroughly competent to discharge the duties devolving upon them in their respective positions. The raising, equipping, and placing the above regiment in the service of the United States was considered a military experiment. It is very gratifying to those who labored day and night for its existence that the project has proved a glorious success. No body of young men in the same capacity have done more efficient work than the Grey Beards. Every officer, whether high or low in command charged with any important trust, has in every instance given entire satisfaction.

The health of the regiment taken through all the seasons of the year will tally with any other in the service. In regard to the number of deaths, they have been less than in most other regiments. And considering the ages of the men, their exposure to all kinds of weather, the amount of labor performed, the preservation of life and health is truly wonderful. Hundreds who taste nothing stronger than tea or coffee enjoy the envied prize of sparkling eyes and rosy cheeks, with a youthful and happy flow of spirits. Should an occasion ever offer itself for these silver-haired patriots to exhibit their pluck and fortitude on the field of blood and carnage, they will be found equal to any heroes that ever drew a sword or cocked a musket. At present, the regiment numbers about seven hundred men, and taking them as a whole, are enjoying fine health and spirits. The men have received their bounty, and all other claims and demands the government has promptly met. Any government whose laws and institutions are so sacred and highly prized as to cause men voluntarily of three score years and ten to leave all the endearments and luxuries of home, giving health and life, if need be, to save that country from desolation and ruin; any nation possessing such elements of power can safely calculate on its strength and perpetuity. Well may the youthful State of Iowa be proud of the honor of sending one of the most extraordinary regiments into the service of the United States government the sun ever shone upon. Historic page will faithfully record their doings, and when they shall have gone to sleep with their fathers, then their posterity will chant in poetic song, the patriotism of their noble and worthy ancestors.

Signed, Justice

Alton, December 25, 1863

The 37th was the unit at the prison during the height of the infamous smallpox outbreak, which took the lives of hundreds of both Confederate prisoners and Federal soldiers, with the older men of the 37th Iowa being especially susceptible.

|

Towards the end of 1863, a smallpox epidemic broke out that resulted in the deaths of hundreds of prisoners and guards. The small prison hospital, which only contained 5 beds, could not accommodate all the men suffering from the disease. The unsanitary and overcrowded conditions at the prison were causing the disease to spread at an alarming rate, and it was decided to quarantine the affected men on Tow Head Island, also known as Sunflower Island, which sat in the Mississippi River just across from the prison.

|

The island was turned into smallpox hospital and cemetery for the prison. Guards had to be threatened with court martial to make them report to the island, for smallpox was just as contagious to the guards as it was to the prisoners. Guards and prisoners were buried together, with as many as 60 bodies in a common grave.

The number of men who died on the island is not well documented. Prison hospital records show an average of five-to-six deaths per day, with at least 900 buried on the island. Estimates of the unrecorded deaths and burials on the island range from 1,000 to 5,000. When the island was filled to the point that no further graves could be dug, infected bodies were ferried back across the river, and then taken up a wagon road to a mass burial site in North Alton, which was located on land leased from a local farmer. This spot today features a large obelisk in memory of all of these fallen son's of the South.

At one time, there were as many men from the 37th as there were Confederates quarantined on Smallpox Island. Most of the deaths in the regiment occurred from September to December of 1863, due to smallpox. The prison reports from the period of late 1863 to early 1864 are almost entirely reports on the epidemic occurring at the prison, which was killing hundreds.

On January 22nd, 1864, Alton said farewell to the men of the 37th Iowa Volunteers, who were then relieved of duty in Alton and sent to Rock Island, Illinois.

The number of men who died on the island is not well documented. Prison hospital records show an average of five-to-six deaths per day, with at least 900 buried on the island. Estimates of the unrecorded deaths and burials on the island range from 1,000 to 5,000. When the island was filled to the point that no further graves could be dug, infected bodies were ferried back across the river, and then taken up a wagon road to a mass burial site in North Alton, which was located on land leased from a local farmer. This spot today features a large obelisk in memory of all of these fallen son's of the South.

At one time, there were as many men from the 37th as there were Confederates quarantined on Smallpox Island. Most of the deaths in the regiment occurred from September to December of 1863, due to smallpox. The prison reports from the period of late 1863 to early 1864 are almost entirely reports on the epidemic occurring at the prison, which was killing hundreds.

On January 22nd, 1864, Alton said farewell to the men of the 37th Iowa Volunteers, who were then relieved of duty in Alton and sent to Rock Island, Illinois.

TO THE CITIZENS OF ALTON AND VICINITY

From the 37th Iowa Volunteers (Grey Beards)

Alton Telegraph, January 22, 1864

Our regiment, the 37th Iowa Volunteers Infantry, is under “marching orders,” and a becoming respect to the amenities of society, not less than the dictates of unfeigned gratitude, require we should make some suitable acknowledgment of the many acts of kindness and liberality manifested toward us during our sojourn of nearly six months in your city.

To particularize or speak of individuals by name would be to make invidious distinction alike undersired, if not disagreeable to all. And while, therefore, we speak in general terms only, we trust at the same time we shall not fail to embalm in grateful recollections your every act of kindly sympathy, from the “two mites” of the widow to the costly and sumptuous repast which celebrated, and made so pleasant the day of our National Thanksgiving.

A writer of judgment and wit has somewhere said, “There are good persons with whom it will be soon enough to be acquainted in heaven.” This may be so, but these are also individuals, with whom it is no common privilege to have been acquainted on earth. And such it is no fulsome eulogy to say we esteem the good people of Alton.

We are old men. Scarcely one of our number but has passed the age of forty-five. While the heads of a large majority have been whitened by the snows of fifty, sixty, and seventy winters. It is not strange, then, that we do not belong to the church of “latter day saints” of pseudo-patriotism. Our earliest and most cherish recollections are the lessons and love of country, taught us by our Revolutionary Fathers. Lessons taught us as only such fathers can teach, while they impressed, and illustrated every precept by the exhibition of unsightly scars, received in defense of our common country on many a varied and well fought field.

About one hundred of our number have “fallen at their post” by the hand of insidious disease, and today the steps of several more of our comrades “halt feebly to the tomb,” dying literally as martyrs to their work; while their sons and grandsons have either “fallen in the harness,” or are today fighting the battles of their country; thus, more than repaying us for all our toil by showing that the “marrow in their bones is true.” And yet, can it be believed that there are those even in Alton, Heaven favored Alton, “So lost to virtue, lost to manly thought, And all the noble sallies of the soul.” As to seek by sneering muendo of licentious tongue, and to asperse our character as men and soldiers, and to make our pathway rough and thorny.

But we have no quarrel with such men – they follow their natural and cherished instincts, and ‘tis not in our hearts to spoil their “occupation,” or mar their joy, for like other buzzing creatures that have just the power to sting, they seem to take an evident delight in the gratification of their feeble natures. All such we leave gladly, and them in the worst of company – we leave them with themselves.

But with the good and the true, the loyal and patriotic, we part with regret, and shall ever cherish the memory of our stay in Alton, and especially the courtesy, kindness, and liberality of her citizens, as among the most pleasant recollections of our campaign life. And now, with our best wishes and most earnest prayers for your temporal and eternal happiness, and hoping to meet again, we reluctantly say goodbye; and ‘may the wings of friendship never lose a feather.’”

G. W. Kincaid, Colonel, 37th Iowa Volunteers

On behalf of the Regiment

From the 37th Iowa Volunteers (Grey Beards)

Alton Telegraph, January 22, 1864

Our regiment, the 37th Iowa Volunteers Infantry, is under “marching orders,” and a becoming respect to the amenities of society, not less than the dictates of unfeigned gratitude, require we should make some suitable acknowledgment of the many acts of kindness and liberality manifested toward us during our sojourn of nearly six months in your city.

To particularize or speak of individuals by name would be to make invidious distinction alike undersired, if not disagreeable to all. And while, therefore, we speak in general terms only, we trust at the same time we shall not fail to embalm in grateful recollections your every act of kindly sympathy, from the “two mites” of the widow to the costly and sumptuous repast which celebrated, and made so pleasant the day of our National Thanksgiving.

A writer of judgment and wit has somewhere said, “There are good persons with whom it will be soon enough to be acquainted in heaven.” This may be so, but these are also individuals, with whom it is no common privilege to have been acquainted on earth. And such it is no fulsome eulogy to say we esteem the good people of Alton.

We are old men. Scarcely one of our number but has passed the age of forty-five. While the heads of a large majority have been whitened by the snows of fifty, sixty, and seventy winters. It is not strange, then, that we do not belong to the church of “latter day saints” of pseudo-patriotism. Our earliest and most cherish recollections are the lessons and love of country, taught us by our Revolutionary Fathers. Lessons taught us as only such fathers can teach, while they impressed, and illustrated every precept by the exhibition of unsightly scars, received in defense of our common country on many a varied and well fought field.

About one hundred of our number have “fallen at their post” by the hand of insidious disease, and today the steps of several more of our comrades “halt feebly to the tomb,” dying literally as martyrs to their work; while their sons and grandsons have either “fallen in the harness,” or are today fighting the battles of their country; thus, more than repaying us for all our toil by showing that the “marrow in their bones is true.” And yet, can it be believed that there are those even in Alton, Heaven favored Alton, “So lost to virtue, lost to manly thought, And all the noble sallies of the soul.” As to seek by sneering muendo of licentious tongue, and to asperse our character as men and soldiers, and to make our pathway rough and thorny.

But we have no quarrel with such men – they follow their natural and cherished instincts, and ‘tis not in our hearts to spoil their “occupation,” or mar their joy, for like other buzzing creatures that have just the power to sting, they seem to take an evident delight in the gratification of their feeble natures. All such we leave gladly, and them in the worst of company – we leave them with themselves.

But with the good and the true, the loyal and patriotic, we part with regret, and shall ever cherish the memory of our stay in Alton, and especially the courtesy, kindness, and liberality of her citizens, as among the most pleasant recollections of our campaign life. And now, with our best wishes and most earnest prayers for your temporal and eternal happiness, and hoping to meet again, we reluctantly say goodbye; and ‘may the wings of friendship never lose a feather.’”

G. W. Kincaid, Colonel, 37th Iowa Volunteers

On behalf of the Regiment

In January of 1864, the men of the 10th Kansas Volunteer Infantry arrived in Alton, and took over guard duties of the prison. The commander of the 10th Kansas was Colonel William Weir, who would earn negative notoriety while in his position of Commander of the Prison in Alton, where he was ultimately court-martialed and removed.

|

Lieutenant Colonel Charles S. Hills

10th Kansas Volunteer Infantry |

The people of Alton were initially very displeased to see the men of the 37th Iowa leave and be replaced by the men from Kansas, as the Iowans were known for their respectful nature while assigned to Alton.

The 10th Kansas were veterans of several campaigns, and large battles by the time they arrived in Alton in 1864. The regiment was assigned to the Department of Missouri and had seen their first major action at the Battle of Prairie Grove. One of the things that would end up being the most popular aspect of the 10th Kansas was the fact that the regiment had a full brass band. The citizens of Alton enjoyed this band, which often marched through the streets playing music and performed for the citizens on numerous occasions. |

HONOR TO WHOM HONOR IS DUE

10th Kansas Regiment has Dress Parade

Alton Telegraph, February 5, 1864

We, with a large number of others, had the good fortune last evening, at the dress parade of the 10th Kansas Regiment, of witnessing the impromptu ceremony of conferring honor upon a deserving and faithful soldier. It seems the night before, Private Willey of Company C, when on guard, had discovered the attempt and prevented the escape of 19 prisoners, for which the Colonel, after calling him out in front of the regiment, thanked and complimented him in a very handsome manner, and recommended him to his Captain for promotion. Our citizens have an opportunity every afternoon, about 4 o’clock, of seeing the best-drilled regiment we have had here. Their manual of arms is superior to the Regulars that were stationed here, and what shall we say of the band? All who wish to enjoy a concord of sweet sounds must go and hear it.

10th Kansas Regiment has Dress Parade

Alton Telegraph, February 5, 1864

We, with a large number of others, had the good fortune last evening, at the dress parade of the 10th Kansas Regiment, of witnessing the impromptu ceremony of conferring honor upon a deserving and faithful soldier. It seems the night before, Private Willey of Company C, when on guard, had discovered the attempt and prevented the escape of 19 prisoners, for which the Colonel, after calling him out in front of the regiment, thanked and complimented him in a very handsome manner, and recommended him to his Captain for promotion. Our citizens have an opportunity every afternoon, about 4 o’clock, of seeing the best-drilled regiment we have had here. Their manual of arms is superior to the Regulars that were stationed here, and what shall we say of the band? All who wish to enjoy a concord of sweet sounds must go and hear it.

The 10th Kansas's service in Alton began during a tumultuous time, during the winter of 1863/64, while the smallpox epidemic was raging. The prison still was overcrowded, and at nearly double its capacity. During the Spring of 1864, some prisoners were transferred out, and by April, the prison boasted fewer than 1,000 prisoners.

While the 10th Kansas was in Alton, the 13th Illinois Volunteer Cavalry and the 17th Illinois Volunteer Cavalry were both briefly posted to assist in guarding the prison in Alton. This period would see numerous prison escape attempts, some of which were successful, an incident in which one man in the 13th Cavalry shot another man in the same unit, as well as a daring robbery committed by members of the 17th Illinois Volunteer Cavalry, which at the time was very dissatisfied with their service in the army and had not yet been supplied with horses.

However, the most serious cause for alarm while the men from Kansas were stationed in Alton was actually due to their commander, Colonel William Weir. Weir was believed to be a southern sympathizer, and was a known friend to Alton "Copperheads". It was alleged that Weir was misusing prison funds, and most egregiously, was spending government funds throwing lavish parties in Alton, at which, many Confederate officers who were prisoners, were allowed to attend. While Weir was in command, he allowed certain Confederate officers to be paroled out of the prison, and visit shops and hotels in Alton. The Confederate prisoners being allowed to walk around the city was very offensive to many of the Federal soldiers who had returned to Alton at the end of their service, or while on furlough.

Eventually, Colonel Weir's behavior and decisions would catch up with him, causing him to lose his command.

While the 10th Kansas was in Alton, the 13th Illinois Volunteer Cavalry and the 17th Illinois Volunteer Cavalry were both briefly posted to assist in guarding the prison in Alton. This period would see numerous prison escape attempts, some of which were successful, an incident in which one man in the 13th Cavalry shot another man in the same unit, as well as a daring robbery committed by members of the 17th Illinois Volunteer Cavalry, which at the time was very dissatisfied with their service in the army and had not yet been supplied with horses.

However, the most serious cause for alarm while the men from Kansas were stationed in Alton was actually due to their commander, Colonel William Weir. Weir was believed to be a southern sympathizer, and was a known friend to Alton "Copperheads". It was alleged that Weir was misusing prison funds, and most egregiously, was spending government funds throwing lavish parties in Alton, at which, many Confederate officers who were prisoners, were allowed to attend. While Weir was in command, he allowed certain Confederate officers to be paroled out of the prison, and visit shops and hotels in Alton. The Confederate prisoners being allowed to walk around the city was very offensive to many of the Federal soldiers who had returned to Alton at the end of their service, or while on furlough.

Eventually, Colonel Weir's behavior and decisions would catch up with him, causing him to lose his command.

JUSTICE AT LAST

Alton Telegraph, September 2, 1864

Colonel William Weer, late in command of the 10th Kansas Infantry, and the unworthy Commander of this post, and the especial pet and associate of the copperheads of this city, has been cashiered by a General Court martial, and retires to private life a disgraced man. The charges it is not worthwhile to enumerate. The following is the finding and sentence:

“After considering the evidence in the case, the Court Martial have sentenced the prisoner, Colonel William Weer, to be cashiered, and to pay over to the commanding officer at Alton, the sum of fifty-five dollars, being the balance due prisoners not yet turned over by the accused to his successor.”

The finding and sentence have been confirmed, and Colonel Weer ceases to be an officer in the United States from August 20, 1864, but is to be retained in arrest by Provost Marshal General until the amount of fifty-five dollars is paid over in accordance with the sentence.

Alton Telegraph, September 2, 1864

Colonel William Weer, late in command of the 10th Kansas Infantry, and the unworthy Commander of this post, and the especial pet and associate of the copperheads of this city, has been cashiered by a General Court martial, and retires to private life a disgraced man. The charges it is not worthwhile to enumerate. The following is the finding and sentence:

“After considering the evidence in the case, the Court Martial have sentenced the prisoner, Colonel William Weer, to be cashiered, and to pay over to the commanding officer at Alton, the sum of fifty-five dollars, being the balance due prisoners not yet turned over by the accused to his successor.”

The finding and sentence have been confirmed, and Colonel Weer ceases to be an officer in the United States from August 20, 1864, but is to be retained in arrest by Provost Marshal General until the amount of fifty-five dollars is paid over in accordance with the sentence.

In late summer, 1864, two companies of volunteers were organized in Mascoutah and Belleville, IL, to guard the prison in Alton, they were given the nickname, "Alton Battalion". These men were initially only enlisted for 100 days service, however they would be used as a cadre for the 144th Illinois Volunteer Infantry Regiment, which was being organized by Colonel Cyrus Hall, and Lieutenant Colonel John H. Kuhn, formerly of the Alton Jaeger Guards.

|

The 144th Illinois Volunteers were recruited almost exclusively in Alton and the surrounding areas. The men of this regiment enlisted for 1 years service, and many were veterans from previous regiments, including Lt. Col. John H Kuhn, and Maj. Emil Adam, both of the 9th Illinois Volunteer Infantry. The 144th Illinois would be the last regiment assigned to guard duty at the prison, and would serve this role until the end of the war.

The 144th Illinois Volunteers were raised expressly for the of guarding prisoners at the prison in Alton and in St. Louis, however, some companies were detailed to guard railroad depots as far South as Georgia. |

Colonel Cyrus Hall - Commander, 144th Illinois Volunteer Infantry

|

By the time the men of the 144th Illinois began service in Alton, the prison was in very poor condition. Although the smallpox epidemic was drawing to a close, disease was still rampant in the prison, which due to it's proximity to the river, made it a haven for mosquitos in the summer, and brutally cold in the winter.

The Alton prison however, no-longer was considered a death sentence, and one news article from February 1864 stated, "Of five hundred persons who were ordered from Alton Prison on Monday for exchange, about one half refused to go, preferring to remain prisoners to going into the rebel army again."

The Alton prison however, no-longer was considered a death sentence, and one news article from February 1864 stated, "Of five hundred persons who were ordered from Alton Prison on Monday for exchange, about one half refused to go, preferring to remain prisoners to going into the rebel army again."

|

Private Thomas S Nichols, Co. H. 144th Illinois Volunteer Infantry

Died at Alton, January 12th, 1865. |

In March of 1865, Colonel Hall was relieved of his duties at Alton, and Lieutenant Colonel John Kuhn was given command of the regiment, and post at Alton.

The 144th Illinois was issued forage caps and dress hats, cords and tassels (for hat trimmings), lined blouses or sack coats, trousers, flannel shirts, flannel drawers, stockings, bootees or shoes, and India rubber blankets (which doubled as waterproof tents in the field). Each man was issued one dress uniform coat, and an overcoat. The 144th was issued with 1853 Enfield rifled-muskets and bayonets, and were issued the standard Federal leather accoutrements. The only known photo of a member of the 144th shows a Private in Company H., with an Enfield musket, a forage cap, a dress coat, and he is not wearing a strap for his cartridge box. |

By April of 1865, many prisoners began to be released. The war was over, and everything began to change. In one instance, hundreds swore an oath and signed on with the 2nd US Volunteer Infantry, and would head West to serve on the Sante Fe Trail at Fort Larned. However, some prisoners remained held, and even as late as May 1865, men were still attempting escape from the Alton Prison. The Alton Prison was officially closed in July, 1865.

PRISONERS TO BE RELEASED

Alton Telegraph, June 16, 1865

We learn from the St. Louis Republican that a list of 112 prisoners, sentenced during the war, and now in Alton prison, has been made out, and the prisoners have been ordered to be released today.

CLOSING OF THE PRISON

Alton Telegraph, July 7, 1865

It will be seen by reference to our daily prison report, that the last of the prisoners left the old Penitentiary this morning. This winds up the duties of the military at this post. But it has not yet been made public what shall be done with the 144th Regiment, which was raised expressly to do guard duty in Alton, but it is generally supposed that the men will be mustered out of service in the course of a few days.

Although we rejoice with all good citizens, that peace has been declared, and that we have no further use for the boys in blue in our midst, still, we have had them among us so long, and their presence has exerted such a healthy influence on the disloyal portion of our community, that we rather regret to have them leave us. During the four years in which we have had them stationed here, there has never been any serious difficulty between them and our citizens. With very few exceptions, their behavior and conduct has been all that could be asked by the most fastidious. Many lifelong friendships have been formed, and although the boys are now, or soon will be, scattered all over the Valley of the Mississippi, still the thoughts and good wishes of our people will attend them, and the friendships formed during their sojourn here will be warmly cherished in many hearts.

Alton Telegraph, June 16, 1865

We learn from the St. Louis Republican that a list of 112 prisoners, sentenced during the war, and now in Alton prison, has been made out, and the prisoners have been ordered to be released today.

CLOSING OF THE PRISON

Alton Telegraph, July 7, 1865

It will be seen by reference to our daily prison report, that the last of the prisoners left the old Penitentiary this morning. This winds up the duties of the military at this post. But it has not yet been made public what shall be done with the 144th Regiment, which was raised expressly to do guard duty in Alton, but it is generally supposed that the men will be mustered out of service in the course of a few days.

Although we rejoice with all good citizens, that peace has been declared, and that we have no further use for the boys in blue in our midst, still, we have had them among us so long, and their presence has exerted such a healthy influence on the disloyal portion of our community, that we rather regret to have them leave us. During the four years in which we have had them stationed here, there has never been any serious difficulty between them and our citizens. With very few exceptions, their behavior and conduct has been all that could be asked by the most fastidious. Many lifelong friendships have been formed, and although the boys are now, or soon will be, scattered all over the Valley of the Mississippi, still the thoughts and good wishes of our people will attend them, and the friendships formed during their sojourn here will be warmly cherished in many hearts.

The Prison after the War

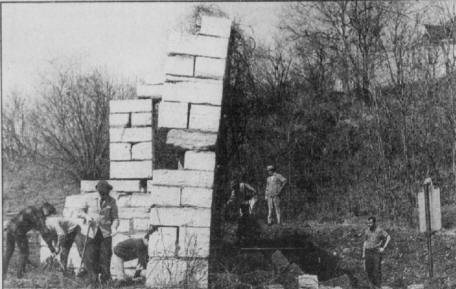

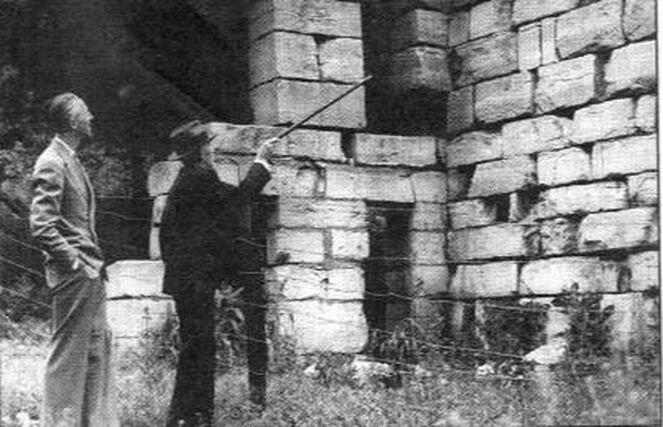

All that remains today of the Alton State Penitentiary / Confederate Prison Camp, which sits at the foot of Williams St. in Alton, Illinois.

After the war, the Federal Government, which had leased the prison from Colonel Samuel Buckmaster, returned the prison to Buckmaster's ownership. Col. Buckmaster attempted to sell the prison as early as 1866, but did not receive any buyers. By 1867, the prison was empty and in disrepair. Sections of wall were starting to collapse, and many of the buildings in the yard had structural issues.

in 1869, with pressure from the State of Illinois, Buckmaster sold the prison grounds to General John Cook, who failed to pay the ammount owed. The ownership of the prison remained in the courts for several years, while the buildings continued to decay and fall apart.

in 1869, with pressure from the State of Illinois, Buckmaster sold the prison grounds to General John Cook, who failed to pay the ammount owed. The ownership of the prison remained in the courts for several years, while the buildings continued to decay and fall apart.

PENITENTIARY IS A PUBLIC NUISANCE

Alton Telegraph, February 15, 1877

There is no disputing the point that the return of several hundred convicts to the old penitentiary grounds in Alton would be a public nuisance of the gravest description. The buildings are in the heart of the business part of the city, and are overlooked by one of the pleasantest residence portions. To locate a penitentiary in such a public place would be a nuisance and an eye sore. But one of the most potent arguments against the removal is the danger that would result therefrom to the health of the city. Within the last two years, a system of water works has been completed in Alton. The pumping works are located on the river bank, directly opposite the penitentiary buildings. Owing to the topography of the locality, the sewerage from the penitentiary would necessarily be discharged into the river not more than a square below the pumping works. There is, we are credibly informed, an eddy in the river at that point, extending as far up as the works buildings. The constant stream of filth from the penitentiary would thus poison the water, be pumped up and distributed over the city, carrying disease and death into every house or factory using water from the works. Even if the penitentiary sewerage were discharged a quarter of a mile below the works, who would be willing to use the river water? This is a serious question for consideration. It might be urged that the penitentiary would dispense with sewerage. To which we reply that such an institution, without sewerage, would become a hot bed of disease and infection, in the very heart of the city.

Alton Telegraph, February 15, 1877

There is no disputing the point that the return of several hundred convicts to the old penitentiary grounds in Alton would be a public nuisance of the gravest description. The buildings are in the heart of the business part of the city, and are overlooked by one of the pleasantest residence portions. To locate a penitentiary in such a public place would be a nuisance and an eye sore. But one of the most potent arguments against the removal is the danger that would result therefrom to the health of the city. Within the last two years, a system of water works has been completed in Alton. The pumping works are located on the river bank, directly opposite the penitentiary buildings. Owing to the topography of the locality, the sewerage from the penitentiary would necessarily be discharged into the river not more than a square below the pumping works. There is, we are credibly informed, an eddy in the river at that point, extending as far up as the works buildings. The constant stream of filth from the penitentiary would thus poison the water, be pumped up and distributed over the city, carrying disease and death into every house or factory using water from the works. Even if the penitentiary sewerage were discharged a quarter of a mile below the works, who would be willing to use the river water? This is a serious question for consideration. It might be urged that the penitentiary would dispense with sewerage. To which we reply that such an institution, without sewerage, would become a hot bed of disease and infection, in the very heart of the city.

|

There was a brief effort to lobby the state to open another Penitentiary in Southern Illinois, and rebuild the Alton prison for this purpose, however this option failed. The prison was ultimately sold in 1884, for the sum of $15,500.

The prison was slowly dismantled over the course of the next few decades, with the original stone tiered blockhouse, which was built in the south-west corner, on the high spot, being one of the last sections to go.. |

A post-war view of what remained of the original blockhouse tiers, built in 1833.

|

The prison was considered to be an eye-sore to many of the citizens of Alton, and was a brutal reminder of the harshness of war. Citizens demanded that the prison be dismantled, as they also believed it to be unsafe, as it was a spot many local children were curious about it. By 1885, the Alton Telegraph was publishing articles about ghostly specters that still haunted the ruins, which would start a legend which continues today.

|

A 20th century view of the remnants of the prison, which was dismantled, from the north-west corner and rebuilt where it sits today in the south-east corner of the lot.

|

The buildings in the yard, such as the blacksmith's shop and the hospital were all dismantled. Almost stone by stone, the prison was torn down over the course of the next century.

In an odd turn, the prisons last days would see families enjoying their Sundays, and children playing on its grounds. The yard and the area known as "Penitentiary Plot" was later turned into a public park. The park was named "Uncle Remus Park" after a fictional character created by Joel Chandler Harris in post-Reconstruction Atlanta. |

Alton lore and legend states that when the prison was torn down, the stones were used in the foundations of various buildings and homes in Alton, which is why so many buildings in Alton are haunted. It's also said that the former site of the prison, once it was a park was known to be haunted. The truth however, is that most of the stones were thrown in the river, and there aren't any confirmed buildings that were built from prison stone.

The area was eventually turned into a parking lot. The final remnants of the prison, a corner of the original cell-block sat in the North-west corner of the lot, on the hillside. In 1970, the wall was moved to it's current position, in the South-east corner of the lot, near the corner of Williams St. and Broadway (Formerly Short St.).

A historical marker sits in front of the ruins, and there are several interpretive signs nearby. The rest of the prison area, including the yard, and former Uncle Remus Park, is still just a parking lot.

Across the river, another historical marker sits near where Smallpox / Sunflower /Toe Head Island was located. This marker is dedicated to the memory of those men lost during the smallpox epidemic in Alton during the Civil War. The island itself no-longer exists. It was almost completely destroyed during the construction of the Locks and Dam in 1936.

In North Alton, an obelisk exists near the spot where most of the prisoners were buried. This land was originally leased by the prison before the war, and the lease continued through the war, and it is the location of as many as 1,500 bodies. The obelisk stands as a singular grave marker for 1,354 soldiers who died as prisoners of war.

Between February 1862 and the end of the war, nearly 11,760 Confederate prisoners entered the prison in Alton. Of those, anywhere between 1,200 - 2,000 men would die at the prison in Alton.